The Bronte Complex

I don’t have dirty little secrets, reader, in my closet, attic or anywhere else. I’m quite happy to admit to my failings – some would say only too happy. All my skeletons have been dusted down and everything is out in the open.

Well, nearly everything.

There is one last secret to reveal. And it’s possibly the dirtiest, most disgusting and depraved secret an English literature enthusiast can have.

I'm not wild about Jane Austen.

Now, I know this sounds sacrilegious but I don’t say it lightly. It’s taken me most of my life to come to terms with it, and if it makes me sound like a philistine, then so be it.

The fact that Pride and Prejudice consistently tops all the most popular classical literature polls is testimony to its enduring success (due in no small part to Colin Firth's infamous wet t-shirt scene in the BBC's 1995 adaptation of the novel – even though it never actually occurred in the text in the first place).

But where is it written that thou shalt like Jane Austen? Where is it set in stone? Heaven knows I tried to like her, I really did. I'll never forget those long, stifling afternoons in Sheffield University's Arts Tower library, stuffing myself with Twix bars and Diet Coke, trying to plough my way through her oeuvre (Mansfield Park is a wonder cure for insomnia I'd highly recommend).

Even film and TV adaptations make me want to gnaw my arm off. Both arms. All that tweeness makes me want to barf. There are only so many tinkling teacups, wafting fans and wistful glances that I can take. And I hate the way people go on about there being "a Lizzie Bennett in all of us", with Austen heroines held up as paragons of femininity and propriety. If that's the only version of femininity available to me, I'll end it all now.

More than any of this, though, I was always told to like Jane Austen; it is always assumed that one must. How can one not?

I mean, when it comes to Austen, I know I could easily be accused of missing the point. I know she's an ever so charming and astute observer of society’s niceties and mores, a radical critic of her milieu, whose novels are supposed to be sophisticated studies of elegant society: good manners, etiquette, decorum. And all that.

She's a master of humour, irony and understated emotion, a mistress at “placing characters in situations of enforced reticence where consciousness of another’s presence heightens emotion and communicates feeling to the reader more intensely – some would say more erotically - than by direct expression”* blah blah blah (are you asleep yet?).

But... so what? What's the point in all this if I find her novels torture to read in the first place? Imagine my relief, reader, when I read this:

Why do you like Miss Austen so very much? I am puzzled on that point. What induced you to say that you would rather have written Pride and Prejudice or Tom Jones than any of the Waverley novels?... I had not seen Pride and Prejudice till I read that sentence of yours, and then I got the book. And what did I find? An accurate, daguerreotyped portrait of a commonplace face; a carefully-fenced, highly-cultivated garden, with neat borders and delicate flowers; but no glance of a bright, vivid physiognomy, no open country, no fresh air, no blue hill, no bonny beck. I should hardly like to live with her ladies and gentlemen, in their elegant, but confined houses. These observations will probably irritate you, but I shall run the risk.

Charlotte Brontë in response to GH Lewis’ review of Jane Eyre, January 12, 1848, taken from Mrs Gaskell's The Life of Charlotte Brontë.

No one ever told me I had to like Charlotte Brontë. I just did. I first read Jane Eyre at twelve after Grandma gave me a collection of novels by the Brontë sisters for Christmas one year. I read it and re-read it and wrote about it prolifically while at university (and yes, I fell for Gilbert and Gubar's Madwoman in the Attic book big time).

Its intimate first person narrative style, direct addressing of the reader and use of colloquial speech made it as accessible as it could be to an adolescent girl, while its sympathetic, socially-isolated heroine, an outsider from the beginning, was someone with whom I could easily identify. If I'd known back then that The Rambler in 1848 had condemned it as "indeed, one of the coarsest books which we ever perused... connected with the grosser and more animal portion of our nature," I'd have probably liked it even more.

There was so much in it that appealed to me. In addition to being heavily influenced by Gulliver's Travels (a text I studied at A-Level and grew to love with a passion), it even had periods in it (more of which later). An extract from an essay I wrote at university shows my insistence at bringing the female anatomy into everything:

It is almost as if Jane should have remained in her mother's womb, never to be born, for the inside world of Gateshead, as well as the outside world, is frosty and cold-hearted. But, born as she is, she emerges from the curtains, an abortion, "trembling" and reluctant, only to be reminded of her inferior status as the poor relation and the obligation she owes to her "superiors": "You have no business to take our books; you are a dependent, mama says; you have no money, your father left you none; you ought to beg and not live here with gentleman's children like us..." And born as she is John succeeds not only in asserting her inferiority in society, but also her inferiority in humanity, as if she is an animal or Darwinian mutation. John abuses Jane both verbally and physically, calling her "bad animal", "mad cat" and "rat" as he hurls the heavy Berwick to hit her, and she falls, bleeding... However, it is not only John who considers her a mutation, for shortly afterwards Miss Abbot and even Bessie agree that, "If she were a nice, pretty child, one might compassionate her forlornness; but one really cannot care for such a little toad as that."

Me in an essay I wrote.

I could never have written essays like that about Austen. Jane Eyre struck me as passionate and revolutionary, as it did most people, and I knew Mr Rochester was a horny Byronic bastard, the stuff of masturbatory fantasy, but the implied, repressed sado-masochism passed me by, really, until only relatively recently. But it's there for those who wish to see it, and Charlotte Brontë enables us to savour it in all its complex gothic glory. In fact the whole novel seethes with the repressed passion of sexual frustration in a way Austen wouldn't have dared contemplate, perhaps reflecting the structures of the patriarchal capitalist society of the time.

|

As for Zamorna, with teeth fast set and the curls of his

bare head shadowing his fierce eyes, he looked hellish...

(Stancliffe's Hotel) |

Nigh on a decade would pass, however, before Brontë explored more convincingly the complex chemistry of adult relationships, how rude and domineering 'masters' can bedazzle and seduce even the most level-headed of heroines, in the shape of Jane Eyre and Edward Rochester. Their relationship is subtly foregrounded even before they meet, as Jane arrives for work at Rochester's house, with observations of "a rookery, whose cawing tenants were now on the wing"; "mighty old thorn trees, strong, knotty and broad as oak": his kindred spirits and familiars, setting the gothic tone and bearing striking similarities with the cruelly moreish, irresistible, tortured Byronic hero at the end of the novel, weakened by the cycle of disguise and deception, charades and masquerades, and his separation from Jane:

...the same strong and stalwart contour as ever: his port was still erect, his hair was still raven black: nor were his features altered or sunk: not in one year's space, by any sorrow, could his athletic strength be quelled or his vigorous prime blighted. But in his countenance I saw a change: that looked desperate and brooding - that reminded me of some wronged and fettered wild beast or bird, dangerous to approach in his sullen woe. The caged eagle, whose gold-ringed eyes cruelty has extinguished, might look as looked that sightless Samson.

Earlier in the novel, their dramatic first encounter, grounded in the stuff of fantasy and fairy tale, firmly establishes their status as equals. He is an inverted knight in shining armour, brought crashing down to earth, his first words left to our imagination: "I think he was swearing, but I am not certain." "Down Pilot!" and "Ugh!" he exclaims as he struggles to compose himself after his fall from his horse.

|

| Mr Rochester by Paula Rego (2002) |

I knew my traveller, with his broad and jetty eyebrows, his square forehead, made squarer by the horizontal sweep of his black hair. I recognised his decisive nose, more remarkable for character than for beauty; his full nostrils, denoting, I thought, choler; his grim mouth, chin and jaw - yes, all three were very grim and no mistake... It appeared he was not in the mood to notice us, for he never lifted his head as we approached...

He continues: "What the deuce is it to me whether Miss Eyre be there or not? At this moment I am not disposed to accost her" [more's the pity].

As for Jane, she sits down, "quite disembarrassed", "obeying his directions", submitting herself to his rude scrutiny and impertinent questioning. "Resume your seat and answer my questions," he orders, before a telling exchange over her paintings: "To paint them, in short, was to enjoy one of the keenest pleasures I have ever known," says Jane. "That is not saying much. Your pleasures, by your own account, have been few," replies Rochester. "I don't know whether they are entirely of your doing; probably a master aided you," he says. "No, indeed!" she insists.

However equal they may be in rank, however skilful she is at matching his wit and meeting his demands, he is her superior in "specific" and "guilty" carnal knowledge. As Gilbert and Gubar say in The Madwoman in the Attic: "...it is he who will initiate her into the mysteries of the flesh." (pp 354-355). The perv.

Subsequent conversations include the setting of boundaries and laying down of unambiguous "rules": "Do you agree with me that I have a right to be a little masterful, abrupt, perhaps exacting, sometimes?" asks Rochester, "on the grounds I stated, namely, that I am old enough to be your father, and that I have battled through a varied experience with many men of many nations, and roamed over half the globe [a list to which one might also add, "and shagged many foreign women"] while you have lived quietly with one set of people in one house?". Boundaries and limitations are issues about which he clearly feels strongly ("No crowding... Don't push your faces up to mine," he barks at poor Adele and Mrs Fairfax), in turn developed into a series of teasing "tests" and challenges, the cut and thrust of verbal sparring.

As the novel progresses Jane and Edward have fun testing each other out in the thrill of the chase, constantly pushing the boundaries between master and servant ("You examine me, Miss Eyre... do you think me handsome?" "No, sir" - Timothy Dalton devotees may well delight in the hilarious irony of this exchange). It is also difficult not to spot shades of Little Red Riding Hood in the immensely humorous, rapid-fire conversation between Jane and Rochester, the big bad wolf who's not too uncomfortable with his feminine side to don the disguise of old gipsy fortune teller, dragging up in "red cloak and black bonnet"* in order to lure the little girl to his lair: "You have a quick ear," says Jane.

"I have; and a quick eye and a quick brain... Why don't you tremble?"

"I am not cold."

"Why don't you turn pale?"

"I am not sick."

"Why don't you consult my art?"

"I am not silly."*

As ever, Jane is not to be fooled. As she later tells Rochester when he whips off his disguise, distinguishing herself sharply from the other ladies of the party: "You did not act the character of the gipsy with me."

In due course these cat-and-mouse mind games develop into what seems to be out and out sadism on Rochester's part. He parades his apparent bride-to-be Blanche Ingram in front of Jane, flirting and ogling, forcing her to watch them together at parties, eliciting reluctant responses: "She's a rare one, is she not, Jane? A strapper, a real strapper, Jane: big, brown and buxom, with hair just like the ladies of Carthage must have had" (an amusing observation – would Austen have written like this? One can almost hear the smack of leather on flesh resounding through his words). In other words, everything Jane is not. Weary, she gives her usual response, the only one she can give: "Yes, Sir." However, when Rochester announces his daughter Adèle is to go to boarding school and Jane is to work as governess to a family in Ireland ("You'll like Ireland, I think: they're such warm-hearted people there, they say"), she finally snaps. In one of the most passionate, iconic literary scenes of all time, Jane squares up to Rochester and strips herself bare of all layers:

Do you think I am an automaton? – a machine without feelings?.. Do you think because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong! – I have as much soul as you – and full as much heart! And if God had gifted me with some beauty and as much wealth, I should have made it as heard for you to leave me as it is now for me to leave you...

Only now does Rochester too shed his disguises and declare his love for her: "It is you only I intend to marry. I offer you my heart, my hand and a share in all my possessions." However, the elaborate dance is not over yet. We can't blame Jane for being initially sceptical, in her determination not to be taken for a fool:

"You play a farce, which I merely laugh at," she replies. "Do you doubt me, Jane?" "Entirely." "You have no faith in me?" "Not a whit." He attempts to convince her and still she resists: "Jane, be still, don't struggle so, like a wild frantic bird that is rending its own plumage in its desperation." Boldly she makes him swear: "Are you in earnest?" Do you truly love me? Do you sincerely wish me to be your wife?" To which he vows: "I do; and if an oath is necessary to satisfy, I swear it." Finally, breathlessly, still in servant mode, Jane gives in:

"Then Sir, I will marry you."

"Edward, my little wife!"

This scene is not without comedy, and neither is it without irony, as barely half way through the text Charlotte Brontë gives us tasty clues as to what's still left unresolved, including Blanche Ingram: "Your bride stands between us," remembers Jane, to which Rochester asserts, "My bride is here" (hmmm... not quite: I think you'll find there's yet another imprisoned in the attic at the top of his house). Rochester is still lying. And while in great fiction masters may lie, the weather never does. Ominously foreshadowing the fatal truth which will out in the end, even trees have feelings:

But what had befallen the night? The moon was not yet set, and we were all in shadow: I could scarcely see my master's face, near as I was. And what ailed the chestnut tree? It writhed and groaned; while wind roared in the laurel walk, and came sweeping over me... Before I left my bed in the morning, little Adèle came running in to tell me that the great horse chestnut at the bottom of the orchard had been struck by lightning in the night, and half of it split away.

In such a superb gothic setting, Jane and Edward's courtship is doomed to be complex, convoluted and painful. Rochester's apparent betrothal to Blanche Ingram is just another charade, part of a grand master plan to secure Jane. But why would he go to so much trouble? What's happened to our rough romantic hero? Is he a horny bastard, or just a bastard? What is the source of his apparent sadistic treatment of Jane? Before we can find out, Brontë gives both Jane and Rochester a chance to enjoy the first flush of their finally declared love and the promise of imminent sex before it is cruelly withdrawn:

"Jane, you look blooming, and smiling, and pretty," said he: "truly pretty this morning. Is this my pale little elf? Is this my mustard-seed? This sunny-faced girl with the dimpled cheek and rosy lips; the satin-smooth hazel hair, and the radiant hazel eyes (I had green eyes, reader; but you must excuse the mistake; for him they were new-dyed, I suppose).

"It is Jane Eyre, Sir."

"Soon to be Jane Rochester," he added: "in four weeks, Janet; not a day more. Do you hear that?"

I did, and I could not quite comprehend it: it made me giddy.

In his eagerness to marry Jane and make her legally his – or so he thinks – Rochester attempts to speed up the process, treating her less like a servant and more like a plaything, a doll, while, in the push and pull of this sado-masochistic relationship, Jane struggles to adjust to the change:

It is your time now, little tyrant," he declares, "but it will be mine presently: and when once I have fairly seized you, to have and to hold, I'll just – figuratively speaking – attach you to a chain like this... I will myself put the diamond chain around your neck, and the circlet on your forehead... and I will clasp the bracelets on these fine wrists, and load these fairy-like fingers with rings." "No, no sir!.. Don't address me as a beauty; I am your plain, Quakerish governess," Jane insists. "I will attire my Jane in satin and lace," he continues, "and she shall have roses in her hair; and I will cover the head I love best with a priceless veil.

Rochester, bless him, is beside himself with sexual excitement.

But Jane cannot wed her prince just yet, and Rochester cannot have his Cinderella, for she still has to undergo his ultimate test, the revelation of the mother of all dirty secrets, revealed at that most propitious of dramatic moments, and echoed throughout countless soap operas centuries later, at the altar. As the priest asks the congregation if they know of any lawful impediment, it is dramatically revealed there and then: Rochester is already married, and has been for many years. How will he get out of this one? He doesn't, although his explanation of how he was duped into a false marriage for economical reasons goes a long way towards explaining his erratic behaviour and sadistic treatment of Jane so far:

Bertha Mason is mad; and she came of a mad family; idiots and maniacs through three generations! Her mother, the Creole, was both a madwoman and a drunkard! As I found out after I had wed the daughter: for they were silent on family secrets before. Bertha, like a dutiful child, copied her parent in both points...

Leading the small wedding party to the third storey of his house and a door hidden by wall hangings, Rochester opens the door to reveal Jane's contrast, as big as Jane is small, her dark "other", the incarnation of all the animal aspects of her womanhood, or in Jane's own words, a "clothed hyena", one of Gulliver's yahoos, another Darwinian mutation:

In the deep shade, in the farther end of the room, a figure ran backwards and forwards. What it was, whether beast or human being, one could not, at first sight tell: it grovelled, seemingly, on all fours; it snatched and growled like some strange wild animal: but it was covered with clothing, and a quantity of dark, grizzled hair, wild as a mane, hid its head and face.

In other parts of the novel Bertha is referred to as "the foul German spectre – the vampyre", "a demon", "a hag", "an Indian Messalina" and "a witch": all symbols of the deviant woman – especially when she is menstruating, as hinted at in the text: after "lucid intervals of days, sometimes weeks", Bertha's attack on Jane occurs when the moon is "blood-red and half-overcast". Upon seeing Rochester Bertha rises up and reaches for his throat and face, the personification of female sexuality at its most terrifying and which must be restrained. Tying her to a chair, Rochester turns to the onlookers:

That is my wife. Such is the soul conjugal embrace I am ever to know - such are the endearments which are solace to my leisure hours. And this," [laying a hand on Jane's shoulder] is what I wished to have, this young girl who stands so grave and quiet at the mouth of hell, looking collectedly at the gambols of a demon.

He dares everybody to:

Look at the difference! Compare these clear eyes with the red balls yonder - this face with that mask - this form with that bulk; then judge me... and remember with what judgement ye judge ye shall be judged!

No wonder Rochester felt he had to test Jane. It is not hard to understand his recent behaviour and his libertine past. He had to find out for himself about his new bride, in order to avoid being duped and making the same mistake twice. Andrea Dworkin said of both Charlotte and Emily Brontë: "Both women had a deep understanding of male dominance... how sadism is created in men through physical and psychological abuse and humiliation by other men", and in an earlier conversation with Jane, Rochester's housekeeper Mrs Fairfax explains, albeit somewhat vaguely, the treatment of Edward at the hands of his father and brother:

I believe there was some misunderstanding between them. Mr Rowland Rochester was not quite just to Mr Edward; and perhaps he prejudiced his father against him... Soon after he was of age, some steps were taken that were not quite fair, and made a great deal of mischief. Old Mr Rochester and Mr Rowland combined to bring Mr Edward into what he considered a painful position, for the sake of making his fortune; what the precise nature of the position was, I never clearly knew, but his spirit could not brook what he had to suffer in it.

The rest of the story involves Jane acting on instinct, refusing to become Rochester's mistress. She resolves to leave him, walking out of Thornfield as "dim dawn glimmered in the yard". Her life post Rochester involves a short period sleeping in fields, living off the fruits of the countryside and begging for food and work before being taken in by the Rivers family: two sisters and a brother, the controlling St John, Rochester's fair "other" ("young... tall, slender... His eyes were large and blue... his high forehead as colourless as ivory... partially streaked over by careless locks of fair hair") who very nearly manipulates her into a passionless marriage and a life of missionary piety and sacrifice abroad.

In true Brontë fashion, however, nothing, neither distance, time nor another man's proposal can keep Jane away from her destiny. Aided by the "wily, windy moors", those perfect conductors and ushers of telepathic thought and feeling, only the celestial telegram can reunite them. Staring at a candle one night, while we later learn that Rochester was also meditating on the moon:

All the house as still... The one candle was dying out: the room was full of moonlight. My heart beat fast and thick: I heard its throb. Suddenly it stood still to an inexpressible feeling that thrilled it through, and passed at once to my head and extremities. The feeling was not unlike and electric shock; but it was quite as sharp, as strange, as startling: it acted on my senses as if their utmost activity hitherto had been but torpor; from which they were now summoned, and forced to wake. They rose expectant: eye and ear waited, while the flesh quivered on my bones.

"What have you hard? What do you see?" asked St John. I saw nothing, but I heard a voice somewhere cry:

"Jane! Jane! Jane!" Nothing more.

Knowing the voice to be that of Rochester, Jane rushes into the garden and answers: "I am coming! Wait for me! Oh, I will come!" She returns to Thornfield.

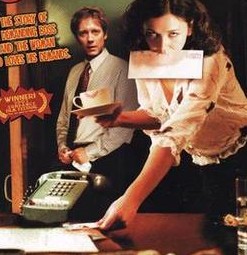

158 years after publication, Jane Eyre still resonates, has lost none of its original power and remains as relevant to contemporary culture as ever, not just to woman with a weakness for older, dark, dominant men. The Wide Sargasso Sea and The Sound of Music are to name but two of her famous 'daughters', while the implied sado-masochism was also unleashed in one of the most fascinating films in recent years, the sensual and earthy Secretary, whose obvious debts must be universally acknowledged.

|

| "Do you want to be my secretary?" |

That said, there's far more to my fascination with Jane Eyre than all the sex there is in it. In Austen's world bosoms may heave until fit to burst, yet, since all of her novels end in marriage, no one actually gets it on until after we turn the final page. Brontë is not too straight-laced and proper to acknowledge what goes on between the covers. Crediting women as complex, intelligent, sexual, spiritual beings capable of living independent lives, she will continue to enthral and captivate for her portrayal of the whole woman, the deviant woman, and yes, dammit, even the northern woman (studying a northern author in a northern city as a northern student, no less).

In an age, reader, where looks are everything, this love story between two self-confessed mingers, two people who don't seem to care about what others think, or about being liked or approved of, is impossible to surpass. As Jane herself admits to Rochester, "I like rudeness a good deal better than flattery." Too bloody right, by 'eck, tha' knows.

___________________________________

* Bernard Richards: Jane Austen and Manners

* ... though his puzzling transvestism, his attempt to impersonate a female gypsy, may be seen as a semi-conscious effort to reduce his sexual advantage hi masculinity gives him (by putting on a woman's clothes he puts on a woman's weakness), both he and Jane obviously recognise the hollowness as a ruse. The prince is inevitably Cinderella's superior, Charlotte Brontë saw, not because his rank is higher than hers, but because it is he who will initiate her into the mysteries of the flesh.

– Gilbert and Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic

*Compare this with Jane's earlier description of the Brobdingnagian Reverend Brocklehurst: "What a face he had, now that his was almost on a level with mine! What a great nose! And what a mouth! And what prominent teeth!"

Elaine Showalter: A Literature of their Own: British Women Novelists from Brontë to Lessing

In addition to the sources already quoted, I am indebted to:

Andrea Dworkin: Letters from a War Zone: Writings 1976- 1987

John Sutherland: Is Heathcliff a Murderer?

Tanya Gold: Reader, I Shagged Him

Comments

Post a Comment